[Spoiler Alert: This constitutes one massive spoiler if you haven’t already seen the movie. I comment on specific situations depicted onscreen based on my experience working as a NASA contractor for over 20 years. So if you’re even slower to see movies than I am, are planning to see it, and prefer to thoroughly enjoy the suspense, then bookmark this blog and read it later.]

First of all, I want to say I thoroughly enjoyed this movie which I finally saw over the holidays while visiting family. My intent here is not to criticize since I believe it was exceptionally well done. It employed a lot of fascinating details, ingenuity and great suspense throughout. Fortunately, Hollywood has come a long, long way depicting NASA-related movies since the movie, Armageddon, which I considered a complete debacle as far as the technical details were concerned.

I suppose being a physicist and geek who worked for NASA as a contractor from 1988 – 2009 are what drive me to pick at technical details, perhaps as a matter of ego to show my knowledge. Whatever it is, I can’t help it, and to me such details are interesting while most normal people would simply enjoy the movie for what it is and give me one of those looks that screams, “What’s your problem, Bozo?” I’ve mellowed on this a bit myself, but I still maintain that a certain level of scientific accuracy is important. But I’m a geek, so what do I know other than it was science fiction that inspired me to become a geek in the first place? Does it really matter if it’s factual? Probably not.

Anyway, “The Martian” is based on the book of the same name by Andy Weir, whom you can learn more about on his Amazon Author page. There’s also an interesting forum on Amazon where various readers have commented on the technical accuracy of the story (or lack thereof), which of course appealed to my inner geek. Having seen and enjoyed the movie, I plan to read the book. I assume that the author did a lot of research putting this story together and can thus take credit for the fact the movie was realistic enough to be credible and even admired by someone like myself. Based on my experience, here are a few comments.

1. My first job with NASA was in the Life Sciences Division at Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. Part of their purview was the well-being of the astronauts. The majority of their experiments conducted on the space shuttle and International Space Station were directed primarily at how exposure to microgravity, increased radiation, close quarters and isolation affected an astronaut’s mind and body. Colonization of distant worlds such as Mars has been a topic of NASA research for many years, including what crops would grow and thrive in conditions different from Earth. Needless to say, being self-sufficient is the ultimate goal.

That said, I suspect that if we had an outpost on Mars that by that time we’d know enough about such things as potential crops that there would have been more for the story’s hero, Mark Watney, to work with besides potatoes which were intended to be consumed as food. I’m reasonably sure that part of the mission would entail planting a variety of things, perhaps for the benefit of the next crew.

Which brings me to my next comment, the length of the movie’s mission being 60 days.

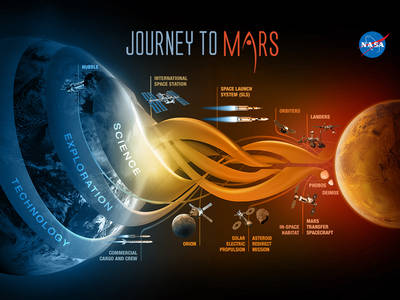

2. It takes a long time to get to Mars, depending on the available propulsion technology, but let’s just say using currently known or at least acknowledged sources, it’s going to be around a year or more. I suppose for the very first mission to the Red Planet that a duration of two months is possible, but I suspect that it would be longer. I also suspect that the habitation module constructed would be one that would be designed to be permanent, part of an elaborate colonization plan and not a primitive throwaway. Given the sophistication of their space vehicle, Hermes, which even had sectors that rotated to create artificial gravity, it’s more likely that part of that spacecraft would have constituted their living quarters and been left behind when their mission ended. This would have lightened the return load as well.

3. I thoroughly enjoyed the connections to previous Mars missions and how they provided resources for Mark to contact NASA. Whether that could actually be achieved I don’t know, but for me it was feasible and clever enough that I had no problem with it. If you’re not at least partly awed by these previous accomplishments that comprise sending and then actually controlling a vehicle on another planet, then you simply don’t understand what it entails.

4. NASA has definitely been known to blow up rockets, not only in the early days of the initial space race with Russia to get to the Moon in the late 50s and 60s, but even more recently as many of you may recall with the Space Shuttle Challenger accident on January 28, 1986. Private rocket companies more recently are having a similar problem. Rocket fuel is highly volatile, systems complex, and problems are inevitable. Thus, when the rocket they put together in record time to send supplies blew up it wasn’t much of a stretch. Anyone who didn’t see that one coming hasn’t been paying attention to the space industry and its explosive history (pun intended).

4. NASA has definitely been known to blow up rockets, not only in the early days of the initial space race with Russia to get to the Moon in the late 50s and 60s, but even more recently as many of you may recall with the Space Shuttle Challenger accident on January 28, 1986. Private rocket companies more recently are having a similar problem. Rocket fuel is highly volatile, systems complex, and problems are inevitable. Thus, when the rocket they put together in record time to send supplies blew up it wasn’t much of a stretch. Anyone who didn’t see that one coming hasn’t been paying attention to the space industry and its explosive history (pun intended).

But there’s more to it that that. Having worked in Safety and Mission Assurance for most of my years at JSC, I was privy to quite a few dirty little secrets. NASA makes every effort to identify every possible hazard and document them all in Hazard Reports. These go far beyond acknowledging the problem itself. Some are classified as Critical, i.e., could cause a problem but not a lethal one, while others are classified as Catastrophic, which entail loss of life and/or millions of dollars worth of equipment. Once hazards are identified, it’s mandatory to identify preventative controls. The severity of the consequences of failure determine how many controls need to be in place. Systems that can cause a catastrophic hazard are required to be three-fault tolerant, meaning three things need to fail before the worst case scenario can occur.

The back shell of the InSight spacecraft is lowered onto the lander in a clean room at Lockheed Martin.

However, there are some systems that defy that level of safety via controls and are thus considered an accepted risk. For example, unless you’re a pilot you probably would never think of a “bird strike” as being in that category, but if a spacecraft on takeoff or landing strikes a bird, it can have dire consequences. Other risks are accepted for a variety of reasons, but it gets complicated so I’ll save further explanation for a future blog, such as some of those “dirty little secrets” that relate to the two space shuttle tragedies. [NOTE:–With the 30th anniversary of the Challenger accident coming up this month, you can watch for one soon.]

Back to the point of the rocket blowing up in the film, besides the inherent danger of propulsion systems in general, bypassed quality assurance inspections or those performed by over-worked technicians would increase the likelihood of problems, making that unfortunate event quite feasible.

5. The next safety-related situation would be the malfunction and subsequent explosion that destroyed Mark’s potato garden. Certainly he did some modifications beyond its original intent, but it’s still unlikely it would have been that fragile. Considering some of the nasty substances that go along on a space mission, explosions are always a possibility. This also refers back to the fact that I doubt their outpost would have been so makeshift in the first place. Mars’ thin atmosphere is not as efficient at destroying meteorites as Earth’s, plus the main asteroid belt lies between Mars and Jupiter, so they’re a bigger problem by proximity as well. I sincerely doubt that NASA would ever erect such a cheesy structure as part of a planetary outpost. This, of course, applies to the matter of the antenna being destroyed as well. Furthermore, as mentioned in the Amazon forum, the force of the Martian wind is lower, given the reduced atmospheric pressure compared to Earth’s.

6. Several of the means employed in the movie were theoretically feasible but unlikely, such as ditching the capsule nosecone and replacing it with canvas or blowing the Hermes module for some extra propulsion. A gravity assist is certainly a possibility since that technique is used routinely for interplanetary exploration missions.

7. Lastly, I’m really skeptical about Mission Control not telling the crew earlier that Mark was alive. That just doesn’t make sense to me. However, NASA employees, no matter what rank they happen to be, are human and subject to bad judgement calls and mistakes, so it’s certainly not impossible. Subsequently, such individuals tend to quietly disappear, probably reassigned to the USA equivalent of Siberia.

In a situation like that in the movie, such a decision would undoubtedly be routed through the Astronaut Office and I suspect that the returning crew would be given that information posthaste. It’s important to know that communications between Mission Control and a manned craft are channeled through a single source known as the Capcom, short for “capsule communicator”, a vestige derived from the early days of the space program. This individual is traditionally an astronaut. This person would undoubtedly be aware of the situation and thus wield considerable influence.

Not distracting the returning crew from their mission simply wasn’t sufficient rationale. Astronauts are human, too, and certainly have emotions which can drive them to do some crazy things in their private lives, but given the story’s circumstances and my experience at NASA, I really believe they’d be treated as the professionals they are and given all available information. They’d be far beyond pissed off to find out they’d been kept out of such an important loop. Whether they’d go “rogue” or not is a possibility but doubtful without full ground support. Spacecraft systems are beyond complex with each one having a team of experts who would assist with calculations for possible solutions.

Consider, as stated in the end of the movie credits, that it took 15,000 people to produce that movie. Far more than that support the space program with each system component typically having a dozen or more engineers that know it inside out. Astronauts couldn’t possibly have the necessary knowledge to make technical decisions that deviate from their training for a specific mission.

If you’re still with me at this point, thanks for listening. I really loved this movie, technical and operational flaws notwithstanding, because this is exactly the kind of film I love. My hope is that it inspires future generations, the ones who will someday walk on Mars, hopefully with a three-fault tolerant infrastructure as opposed to what astronaut Mark Watney had to deal with in “The Martian”.

You can pick up a DVD of the flick on Amazon here.

Mars Photos courtesy of NASA

Marcha, thank you for providing the clear and detailed clarification on so many parts of the movie I had wondered about precisely because I do not have a NASA insider’s views and experience. I wish I could have gone to the movie with you and had a discussion about it right after that with you! Your thoughtful post here makes up for that missed opportunity.

LikeLike

Thank you so much! I wish we could have seen it together, too.

LikeLike

Pingback: Marcha Fox Blog – A Nasa Insider’s View Of “The Martian” Movie Version | Ceri London

Loved the movie. Fascinating post.

LikeLike